Royal Enfield's long history as a motorcycle maker has many valleys and many mountains. So it's no surprise that reading its history leads to surprises around every corner.

I'd vaguely accepted that Royal Enfield introduced foot shifting as an alternative to hand-operated gearshifts in 1933, along with their new Bullet model. Foot shifting was a big selling point, as it eliminated the need to take a hand off the handlebars.

Royal Enfield actually had tried a foot shift much, much earlier, on its 1911/1912 Model 170 ladies step-through motorcycle. That attempt lasted only one year. Perhaps not enough ladies wanted to go motorcycling then.

Royal Enfield tried again, in 1924, and this time not just on the ladies' model. It would have a fancier heel-and-toe lever that incorporated the clutch. It was the brain child of founder and managing director Robert Walker Smith. His brilliant idea apparently worked just fine, but, again, the timing was wrong.

|

| Two-speed Royal Enfield foot shift, circa 1924. This example appeared on eBay in April, 2024. |

I'd seen a reference to early foot-shifting in Jorge Pullin's My Royal Enfields blog, but failed to realize the significance of it.

The light bulb went on during a recent re-reading of Peter Miller's book "Royal Enfield, The Early History, 1851-1930."

Let's start with the innovation of shifting gears in the first place.

When introduced in the 1910s Royal Enfield's unique two-speed gearbox was revolutionary. Neatly combining gearshift and clutch in one, it shifted drive force between either of two unequal size chainwheels (you got neutral if neither was engaged).

The two-speed Royal Enfield boasted of a considerable improvement in hill-climbing power and engine flexibility compared to single-gear machines (although, being cautious, the company continued to sell those, too, in 1910).

To choose between gears, the adventurous Royal Enfield rider rotated a lever extending above the flat tank. This looked something like the control lever of a trolley car.

|

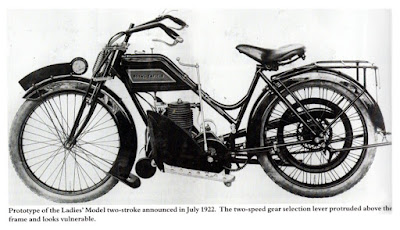

| Prototype Ladies' Model had hand-shift lever, but production models would get the innovative foot shift. Photo from Peter Miller's "Royal Enfield, The Early History." |

And that eventually became a problem, Peter Miller writes in "Royal Enfield, The Early History, 1851-1930."

"Hand changing of gears would remain in use for many years, but the tram-type of lever was becoming antiquated. Also it was impractical on drop frame (ladies') models due to the lack of an upper anchorage point. Robert Walker Smith's solution was to adapt the Enfield Patent two-speed gear to foot operation.

"His revised design is presented in Patent application number 23,132/23 which was titled 'Improvements in or relating to variable speed gear mechanism, suitable for motor cycles and the like.'"

Basically, the trolley-car style hand controller was replaced with a rocking heel-and-toe pedal. This elegant solution was standardized in 1924 on all but the cheapest of Royal Enfield's single-cylinder models.

|

| Drawing from Peter Miller's "Royal Enfield The Early History." |

Almost as soon as it was invented, though, the clever foot-change pedal would be dropped.

Peter Miller explains:

"The Royal Enfield patent two-speed gear had served the company well over many years. It provided direct drive on both gears and with its self-contained clutch was simple for the rider to master. Arguably two-speed gears were perfectly adequate for the low-tuned engines of the period, but by this time (1924) most manufacturers were offering machines with three-speed gearboxes. For Enfield to remain competitive it was necessary to follow the trend and the Royal Enfield two-speed gear would be phased out over the next two years.

"The new (for 1924) mid-range machines were offered with the Royal Enfield two-speed gear as standard, but with an option for a three-speed Sturmey-Archer three-speed gearbox and hand change," Miller writes.

For 1925 the foot-change was limited to only Royal Enfield's two-stroke models. For 1926 the two-stroke models themselves were redesigned, and now carried two-speed constant-mesh gearboxes with the hand-operated gear change lever.

The foot shift was gone.

Illustrations in Peter Miller's book show that a way was even found to attach the two-gear hand-shift to the ladies' open-frame models of 1926.

Wasn't this a step backwards?

Would not some customers have preferred the simplicity of the rocking foot lever for gear and clutch to the complication of a hand shift for one hand and the attendant clutch lever for the other?

Royal Enfield apparently didn't think so. Not at all.

According to Peter Miller's book, the company even constructed a prototype drop-frame model equipped with a 347cc JAP motor and three-speed Sturmey-Archer gearbox.

But what were they thinking? It wouldn't have been safe to wear a skirt on that hot rod, and why ride a drop-frame model in pants?

In all of motorcycle history, the drop-frame 350 may be the best example of answering a question no one ever asked.

But the foot-change gearbox shift would be back. Ironically, its reappearance would be linked to another Royal Enfield innovation: the neutral finder.

They had a two PRIMARY drives. Two sets of chains from the engine sprockets to the clutch sprockets drove the final drive shaft and sprocket. The clutch sprockets were free running on the "Gearbox" mainshaft until an internal expanding band clutch was engaged. A rocking pedal moved a wedge that expanded the clutch band. Neutral was when the wedge was positioned between the clutches.

ReplyDeleteThank you for a much improved explanation.

Delete