|

| Royal Enfield's Christmas party for children, December, 1945. |

Two-hundred-thirty children gathered in Royal Enfield's employee canteen, built for the use of wartime factory workers, to welcome Christmas, 1945.

The children were sons and daughters of Royal Enfield employees, and children of members of the armed forces. There was a sing-along, a magic show, a visit from Santa, and ice cream, The Redditch Indicator reported on Dec. 24.

And there was peace.

World War II was over. Royal Enfield could foresee going back to making motorcycles for the civilian population of Britain, the Commonwealth and the world. But first there were wounds to bind, thanks to be given, and stock to be taken.

Royal Enfield's scrapbooks of press clippings are in the archives of the Royal Enfield Owners Club UK. REOC archivist Bob Murdoch shared these with me, recently.

So far, I have blogged about the scrapbook entries for the 1960s, and the war years of the 1940s.

Let's open the scrapbooks and see what the press had to say about Royal Enfield as the greater of the two World Wars approached its end.

"Figures in which the nation -- not least, motor cyclists -- can take pride," The Motor Cycle had reported on Dec. 7, 1944.

The occasion was the release of a Government White Paper showing that the British motor cycle industry "has supplied the Services with, among numerous other articles, 343,000 motor cycles in less than five years."

"Now for a surprise for many. Well over a third of all the wheeled vehicles were motor cycles -- those vehicles which, at the outbreak of war, were regarded by many as having little military significance."

The Motor Cycle was right to crow. But victory was still not at hand. The enemy would begin the Battle of the Bulge only nine days later. There was more war ahead and more war work to be done.

|

| Royal Enfield workers aid blinded veterans. |

Britain's St. Dunstan's school for the blind had served blinded service members since the First World War. In 1945, with new victims of war to serve, the institution appealed to manufacturers for tandem bicycles, so that blinded soldiers might enjoy riding, with nurses up front doing the steering.

Most firms replied that they could do nothing to help. But sales manager C.F. "Freddie" Blandon of Royal Enfield found six bare tandem frames, Cycling reported on April 25, 1945.

Blandon begged Enfield's suppliers for the pieces needed to complete the bicycles-built-for-two. Enfield employees, Edgar Keyte, nearly 70, and Ern. Ewins, over 60, volunteered to assemble the bikes on their own time in a corner of the factory.

Their good deed garnered a lot of press coverage.

|

| Woman dispatch rider and many women workers at the Triumph Factory. |

"400,000 Motor Cycles for the Services!" The Motor Cycle reported on Dec. 5, 1945, updating the total now that the war was finally over. A brigadier general accepted delivery of the 400,000th motorcycle from Edward Turner at the Triumph factory.

The general turned to smiling dispatch rider Pvt. Connie Baker of the Auxiliary Territorial Service and she rode off on the 400,000th machine with a message about it addressed to Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery.

By Nov. 8, 1945, the motorcycling press could reveal Royal Enfield's postwar models for 1946. There would be a civilian version of the two-stroke, 125cc Flying Flea, with its rubber-band front suspension, and 350cc Model G and 500cc Model J four-stroke singles with telescopic front forks and the new "special neutral lever."

|

| Illustration of new neutral finder shows it sticking up with T-shaped handle. In production it was a horizontal lever operated by the heel. |

This was the foot-operated neutral finder, beloved by Royal Enfield riders for decades to follow. (This useful lever appears on my 1999 Royal Enfield Bullet, built in India, and I use it constantly.)

But early riders were not so sure. A piece in The Motor Cycle worried that it would be impractical in winter.

"Men with frost-proof circulation will make no protest. But if one had a bad, elderly circulation, plus very long legs, the gadget may not fully meet the case," the author wrote.

The writer preferred a hand gear-change lever "unless (a) you are so clumsy that you simply have to look down to find a notch, or (b) ride so fast that it is unsafe to take a hand off the bar."

Another writer suggested that the neutral finder be a small lever operated by hand, in combination with the clutch. No one seemed to like the idea of human riders with only two feet having to operate three foot pedals, but in practice the heel-operated neutral finder was a natural.

With the neutral finder and telescopic forks, the Royal Enfield's Model G and Model J for 1946 were indeed updated compared to their wartime ancestors. But there was another model, the 350cc Model CO.

Based on the military WD/CO, it would lack the "neutralizing lever," and use the old girder forks, Export Trader revealed in December, 1945. These civilian CO models would appear in black instead of olive drab paint but they were really war surplus motorcycles.

|

| Road test of the 1946 Royal Enfield Model G. A handsome machine? |

Motor Cycling carried a full road test of the new Royal Enfield Model G on June 13, 1946, pronouncing it not at all a warmed-over military motorcycle, but "a machine with a new and sparkling personality."

The article pointed out something I'd never noticed before: the deeply valanced front fender is sprung: that is, it's attached to the part of the forks that doesn't move, thereby eliminating the need for fender stays.

I disagree with the article's conclusion that the result is "a very clean appearance," but it must have struck motorcyclists at the time as an improvement over the cluttered look of girder forks.

The scrapbooks feature page after page of clippings devoted to coverage of trials events in which Royal Enfields competed. The impression given is that this peculiar form of competition dominated motorcycle sports in this period.

|

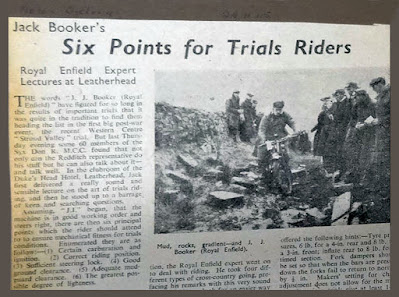

| Jack Booker was Royal Enfield's ace trials competitor. |

Trials competitions were slow, with riders judged by how often they had to put a food down in the midst of complex maneuvers on rutted and even flooded trails. Scrambles, in contrast, were high-speed runs off-road, with motorcycles vaulting over ridges.

A talk by Royal Enfield technical director R.A. Wilson-Jones was the subject of an article entitled "Applying Trials Knowledge to Everyday Riding" in the March 21, 1946 issue of The Motor Cycle.

Royal Enfield's trial ace Jack Booker was present at the talk. Asked why motorcycle makers supported trials events so strongly, yet "gave a miss to scrambles," Booker replied that he "regarded scrambles as freakish."

Pressed on this, "Jack reiterated his view that scrambles were freakish, and said that if anyone bent their forks in a scramble (manufacturers) would not alter the forks because they knew they were perfectly all right for ordinary work."

So, there!

Is this the sound of the British motorcycle industry being stuck in its ways? (Two decades later, Royal Enfield would promote its Interceptor as a "desert sled," pictured racing with its front wheel in the air.)

More than once Wilson-Jones was quoted in the press on the value of trials. Racing emphasized speeds most riders would never use, he wrote, while trials tended to produce docile, good-mannered motorcycles, and trials trained riders to control them in adverse conditions.

Royal Enfield was good at trials, rejoiced The Redditch Indicator (perhaps somewhat biased in favor of the home-town company), in October, 1946:

"After carrying all before them in the Alan Trophy Trial, Royal Enfield machines and riders once again made motor cycle history -- proving their consistency of enterprise, and leaving no doubt in motorcyclists' minds as to who is going to set the Trials pace this season -- by recording a further striking list of successes in the West of England Trial on Saturday."

And then, in February, 1947, came this report in the Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader: "Electricity Cuts Bring Production to a Standstill." Government limits on use of electricity during severe cold and snow stopped factory work, including all motorcycle manufacturing.

Royal Enfield kept some employees at work doing a "spring clean" of the factory although they were working without heat. Britain shivered for a fortnight, and then experienced flooding when a thaw set in.

|

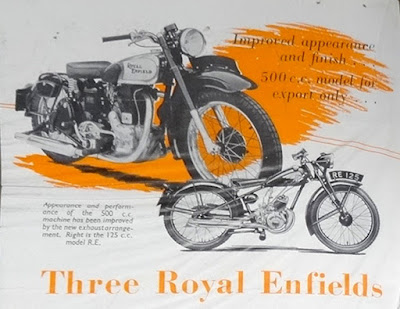

| Royal Enfields for 1948. The Model J 500 was now the J2 with two exhaust ports and a shiny silencer on each side. |

A December, 1947 article in Export Trader reported that Royal Enfield would continue in 1948 with three models: the 125cc two-stroke and 350 and 500cc four-stroke motorcycles. The three-model policy was really a two-model policy because it was expected that all the 500cc Royal Enfields would be exported. (Before the war, Royal Enfield had offered 15 different motorcycle models!)

Reminders of war persisted at every turn. Eric A. Fish wrote to The Motor Cycle to describe his 10-day trip to France and Switzerland on a Royal Enfield 350. He advised that it was absolutely essential to bring food, as little or no food could be obtained in France, although beer and wine were plentiful.

Gas was still rationed on the continent, but there was no trouble getting coupons for it, and it was better than the fuel in Britain.

"Petrol in both countries is perfect, and I found a tremendous thrill in driving the machine on good petrol... the Royal Enfield performed magnificently," Fish wrote.

At home, Britain was getting by on poor quality rationed gasoline until the government ended even this, in late fall of 1947. There would be no gas whatsoever, except for business, farmers and hardship cases. (No wonder the press paid so much attention to the high miles per gallon possible on the Royal Enfield 125cc two-stroke.)

Yet trials contests went on!

"The Ministry of Fuel and Power granted the 160 competitors a petrol allocation, recognizing the value of such tests as the Colmore in proving British motor cycles the best in the world and placing them high in the export list," The Birmingham Mail reported on Feb. 21, 1948.

Spectators who arrived at motorcycling contests by private car, motorcycle or taxi would face questioning by police, however. With access to gasoline seriously restricted there was an active black market for it.

Former Lt. Peter Coleby, D.F.C., wrote to The Motor Cycle:

"The present prospect does indeed seem bleak and it appears to me that the loss to morale throughout the country is not going to balance the saving of dollars. The value of things that helped to maintain morale during the war was recognized to the full, and, in my opinion, that aspect of the abolition of basic petrol should be reconsidered before it is too late."

|

| There was gas for trials contestants at the Colmore. But there was more exciting news: reporters got their first peek at Royal Enfield's most exciting new development yet. |

Morale was about to improve, at least as far as exciting new motorcycles went. Royal Enfield had history-making good news for British motorcycle riders, and the press was about to announce it.

Read what the future held here.

No comments:

Post a Comment